This class primarily focused on various methods of parallel computation. In particular, we studied how serial programs can be converted to parallel programs and the cost/benefit analysis of doing so.

The main environments we used were OpenMP, MPI (Message Passing Interface), and environments for GPU programming such as CUDA.

The class was split into three projects, each focusing on a different environment for parallel computation.

Project 1: Hand-Tuned DGEMM on AWS Graviton3

In our first project, we started from a naive dense double-precision matrix multiply and were asked to turn it into a high-performance GEMM running on a single core of AWS Graviton3 (c7g.medium). The target was to get close to, or even beat, OpenBLAS on this specific setup—without changing the basic

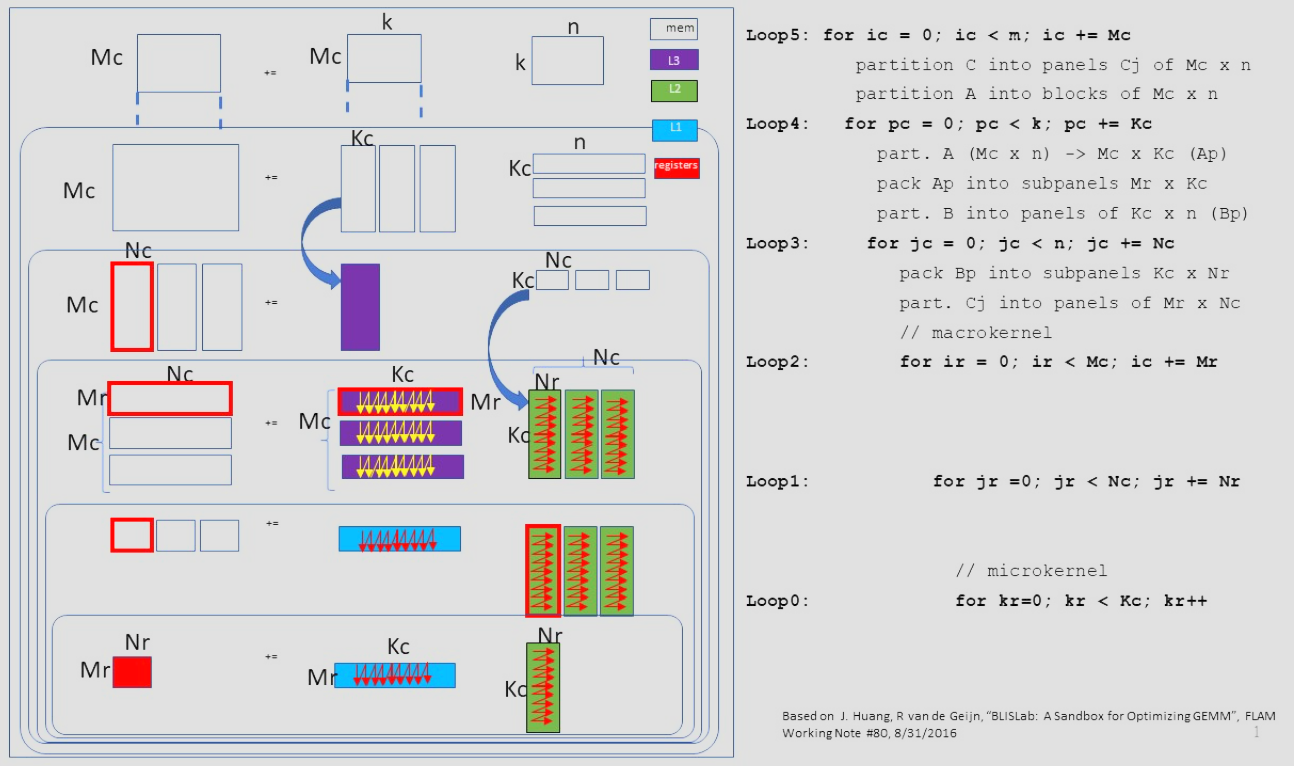

The core idea is that you don’t multiply whole matrices at once; you break them into tiles that fit the memory hierarchy:

In practice, that meant writing packing routines for A and B so the microkernel sees nice, contiguous micro-panels instead of strided, cache-unfriendly data.

On top of those packed panels, we implemented a fixed-size SVE microkernel that computes one

The overall code structure looked like this:

// Macrokernel (simplified)

for (int ic = 0; ic < m; ic += Mc)

for (int pc = 0; pc < k; pc += Kc) {

pack_A(A + ic*k + pc, ...); // Ap: Mc x Kc

for (int jc = 0; jc < n; jc += Nc) {

pack_B(B + pc*n + jc, ...); // Bj: Kc x Nc

// Walk tiles of size Mr x Nr

for (int ir = 0; ir < Mc; ir += Mr)

for (int jr = 0; jr < Nc; jr += Nr)

microkernel_sve(...); // Figure 8

}

}

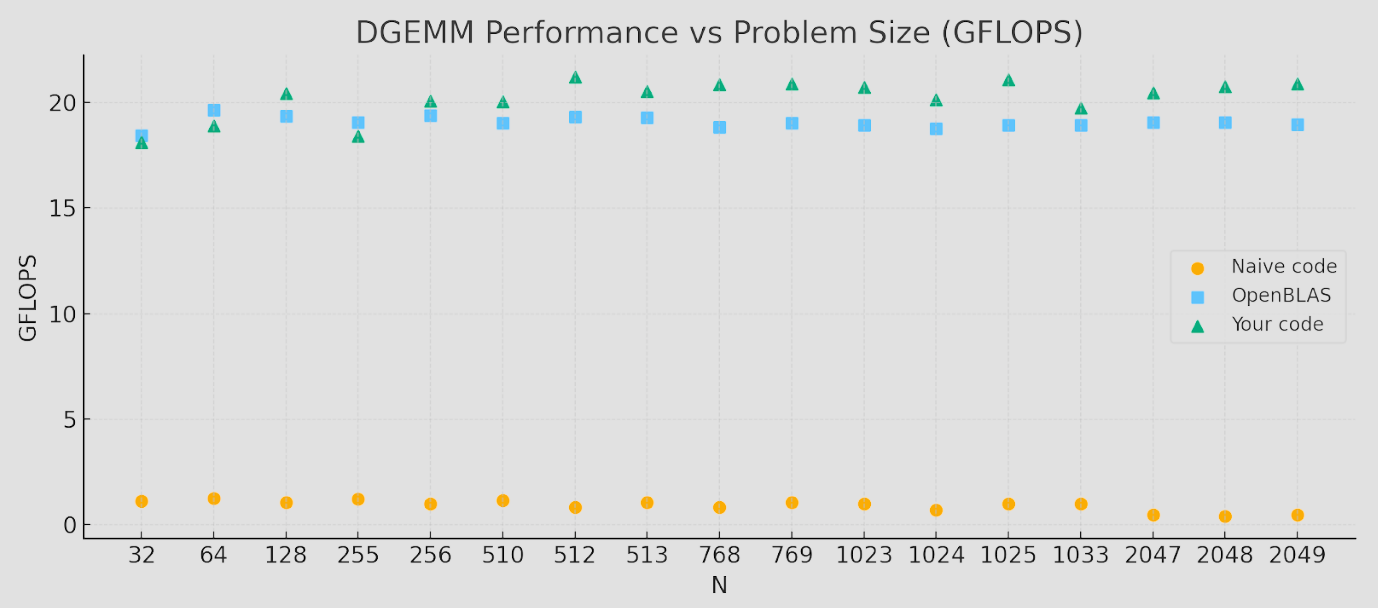

By the end, the numbers looked roughly like this:

So on this particular hardware and sizes, our tuned kernel slightly outperformed OpenBLAS.

Project 2: High-Performance CUDA GEMM on Turing (T4)

In the second project, we moved from CPU to GPU: starting from a naive CUDA matrix multiply (Hwu & Kirk–style, totally global-memory bound) and turning it into a high-performance single-precision GEMM on an NVIDIA T4 (Turing) GPU on AWS (g4dn.xlarge). The target was to get into the same ballpark as cuBLAS on this hardware, while still using the standard

The core idea, mirroring the figures in the handout, was to tile the computation at several levels: each thread block owns a big BM×BN tile of C, we stage the corresponding BM×BK tile of A and BK×BN tile of B through shared memory, and inside that tile each thread computes a tiny TM×TN micro-tile entirely in registers.

In code, the kernel ends up looking conceptually like this:

// One block computes a BM x BN tile of C

__global__ void mmpy_kernel(float* A, float* B, float* C, int N) {

// Figure out which BMxBN tile of C this block owns

int blockRow = blockIdx.y;

int blockCol = blockIdx.x;

// Each thread gets a TMxTN micro-tile in registers

float acc[TM][TN] = {0};

for (int bk = 0; bk < N; bk += BK) {

// Cooperative load of A and B tiles into shared memory

load_Asub_to_smem(A, blockRow, bk, ...); // BM x BK

load_Bsub_to_smem(B, bk, blockCol, ...); // BK x BN

__syncthreads();

// Compute on this K-tile

#pragma unroll

for (int k = 0; k < BK; ++k) {

float a_vals[TM] = load_A_row_fragment_from_smem(...);

float b_vals[TN] = load_B_col_fragment_from_smem(...);

fma_outer_product(acc, a_vals, b_vals); // TMxTN outer product

}

__syncthreads(); // (optional double-buffer swap here)

}

// Write each thread's TMxTN micro-tile back to C

store_C_microtile(C, blockRow, blockCol, acc, ...);

}

On top of this basic structure, we layered in the fun GPU-specific tricks such as warp-aligned layouts (warps map cleanly to rows/cols), multiple outputs per thread for ILP, some double-buffering in shared memory, and a bit of autotuning over (BM, BN, BK, TM, TN, bx, by). Our best configuration used 512 threads per block with a reasonably sized per-thread micro-tile, and hit around 4.8 TFLOP/s on large matrices like

Project 3: MPI Stencil Simulation on SDSC Expanse

In the third project, we left single machines behind and went fully distributed: we took a scalar 2D wave simulator and turned it into an MPI application that runs across many cores on SDSC Expanse. The physics is a simple 2D wave equation on an

The basic update at each grid point looks like:

We kept the existing code structure (JSON configs, obstacles, sine sources, plotting) and swapped in an MPI-aware backend. The global grid is split into a 2D grid of MPI ranks (px × py). Each rank owns a rectangular subdomain plus a 1-cell halo on all sides:

At every timestep, each rank:

- Exchanges ghost cells with its up/down/left/right neighbors (halos), using nonblocking

MPI_Isend/MPI_Irecvfor rows and packed columns. - Applies the 5-point stencil on its interior points (no branches), including a fast path that works directly with flat arrays for better cache use and vectorization.

- Handles boundaries: outer ranks apply the absorbing boundary condition on the physical edge; interior interfaces are handled purely through the halo exchange.

- Periodically reduces statistics (

MPI_Reduceon max and sum of squares) so rank 0 can print global max amplitude and energy.

Conceptually, the timestep loop looks like:

for (int t = 0; t < niters; ++t) {

ghostExchange(u); // halos → ghost cells

// interior stencil (no ghosts)

updateInterior(u_prev, u_cur, u_next, alpha);

// physical outer boundary (ABC)

updateOuterEdges(u_prev, u_cur, u_next, alpha, isGlobalEdge);

swap(u_prev, u_cur, u_next);

}

Once the MPI version matched the uniprocessor wave260uni on max / SumSq, we pushed it onto Expanse and studied scaling. With a good 2D process geometry (near-square px × py), the code scales cleanly from a single core up to the hundreds of cores the assignment asks for, with ghost-cell communication staying a modest fraction of runtime even at large core counts.