This project was part of a UCSD's CSE 110 class, and the goal wasn’t to ship a perfect website (our website is quite silly)—it was to practice agile software development, teamwork, and the kinds of processes real teams use (sprints, meetings, ADRs, CI/CD, code quality gates, etc.). The actual “product” we built was a fun vehicle for learning: a Panda Express-themed fortune-cookie ordering game that ends with a fortune (and even shows nutrition totals).

Below is a walk-through of the parts I worked on and what I learned along the way.

The idea, in one sentence

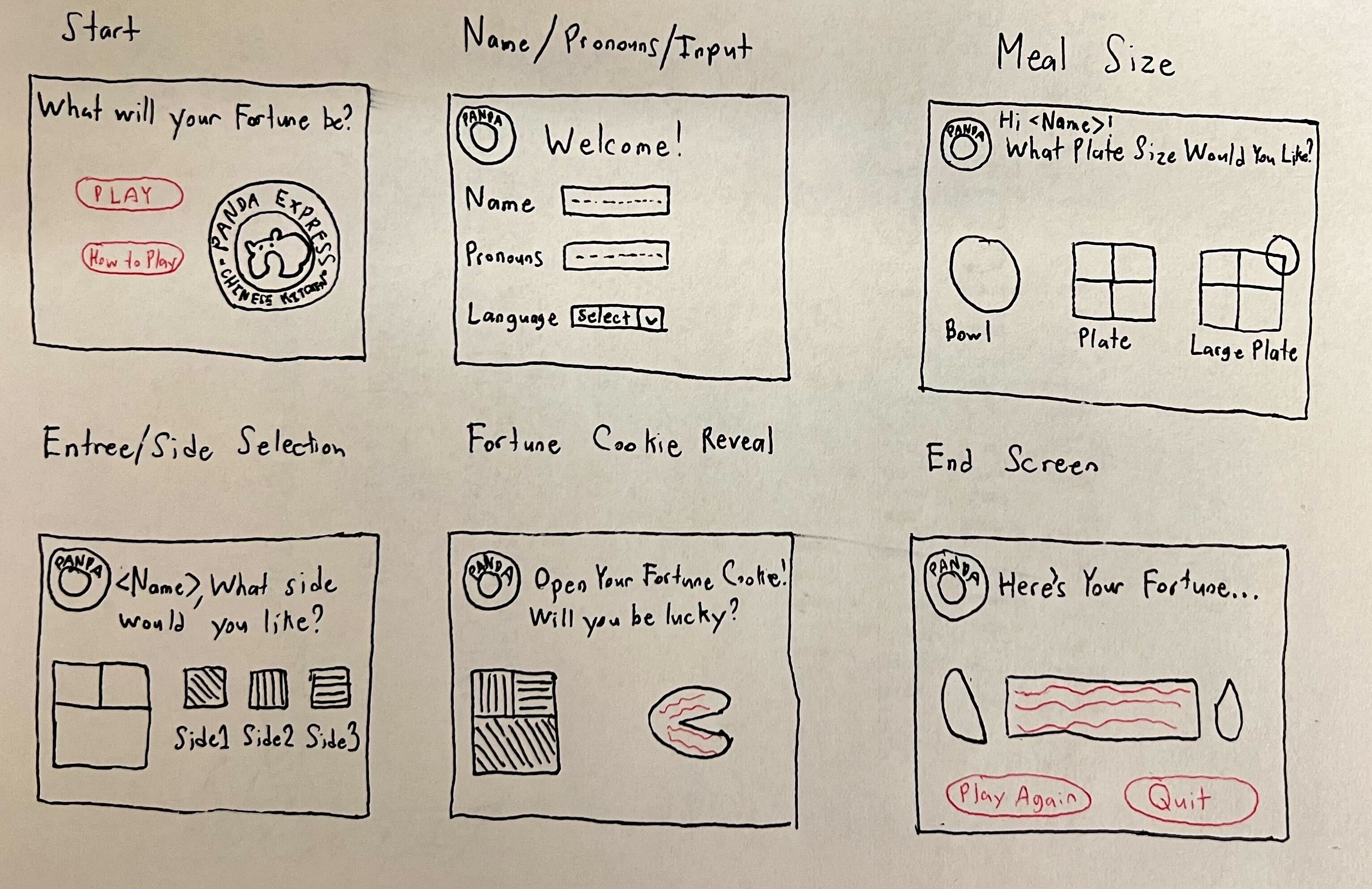

Users click through a mock Panda Express order (meal size → side → entrees), and the choices affect a score that determines what kind of fortune they get—plus we total up nutrition facts and show them at the end.

Agile-first from day one

Instead of “everyone code until the deadline,” we treated this like a mini team project:

- Kickoff + team cadence meetings to set expectations and organize

- A clear pitch + decision points as our scope evolved

- Sprints with reviews and a retrospective

- ADRs (Architecture Decision Records) so decisions were documented instead of forgotten

A few milestones from the meeting notes:

- April 17, 2023 — Kickoff meeting: expectations, repo setup, intro video plan

- April 22, 2023 — Design meeting: theme decisions and feature prioritization

- May 8, 2023 — TA pitch meeting: adjust product flow (force fortune cookie at end)

- May 19–27, 2023 — Sprint planning + review + retrospective

- June 4, 2023 — TA meeting: hard deadlines (code freeze June 12, presentation June 14)

That cadence made the work feel structured—like we were iterating toward something instead of rushing in a panic at the end.

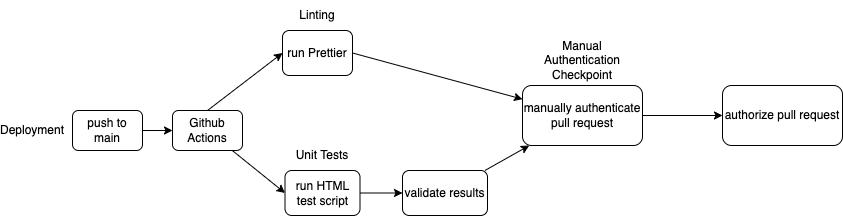

My biggest “process” contribution: CI/CD + quality gates

One of the most valuable parts of the project for me was building out the automation around the code: linting, tests, and making sure every push got checked.

CI pipeline design

We wrote up a Phase 1 CI/CD plan and kept it lightweight: every push should run the same checks so the repo stays healthy.

Linting workflow (GitHub Actions)

We enforced formatting + lint rules via CI so style didn’t become a constant debate in review.

# .github/workflows/linter.yml

name: Lint checker

on: [push]

jobs:

format:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

with:

ref: $

- uses: actions/setup-node@v2

with:

node-version: "18.x"

- name: npm install

run: npm ci

- run: npm run lint

- name: Commit changes

uses: stefanzweifel/git-auto-commit-action@v4

What mattered here wasn’t just “make it green,” but learning how teams reduce friction:

- Prettier keeps formatting consistent automatically.

- ESLint catches common JS issues early.

- Running it on every push makes quality the default, not a last-minute scramble.

Our lint command combined both tools:

"scripts": {

"lint": "npx prettier --write . && eslint --fix ."

}

Test workflow

Even simple unit tests teach the discipline of verifying behavior as you iterate.

# .github/workflows/tests.yml

name: Tests

on: [push]

jobs:

tests:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

strategy:

matrix:

node-version: [18.x]

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

- name: Use Node.js $

uses: actions/setup-node@v2

with:

node-version: $

- name: npm install

run: npm ci

- name: tests

run: npm test

Documenting decisions like a real team (ADRs)

In class projects, it’s super easy to make a big decision in a meeting and then… nobody remembers why two weeks later. ADRs solved that.

Style enforcement decision (Prettier)

We captured why Prettier was worth it: consistent formatting across markdown/JSON/JS/HTML/CSS without endless style arguments.

A decision I specifically owned: JSDocs in a separate repo

One pain point: auto-generated JSDocs didn’t always play nicely with our lint rules. Instead of disabling linting or letting docs break CI, we made an explicit decision:

Generate and host JSDocs in a separate repository so CI can stay strict and clean.

That’s the kind of “engineering compromise” that comes up constantly in real teams: protect the pipeline, keep docs, and avoid flaky failures.

The “product” side: game logic + structure

Even though the site wasn’t the primary learning goal, we still needed something cohesive enough to support our process.

State-driven UI flow

The UI is basically a sequence of pages (front page → meal size → side → entrees → cookie reveal → fortune → nutrition). Instead of navigating routes, we just hide/show sections.

const pages = [

"front-page",

"meal-size",

"side",

"entree-1",

"entree-2",

"entree-3",

"fortune-cookie-reveal",

"fortune",

"nutrition-facts",

];

export function hideAllPages() {

pages.forEach(

(page) => (document.getElementById(page).style.display = "none"),

);

}

That structure made it easy for multiple people to work without stepping on each other: one person could focus on HTML sections, another on CSS, another on the state machine.

The “fortune engine”

The core mechanic is a gameObject that tracks:

score(good/bad choices)weird(chance of weird fortunes)nutritiontotals across selections

getFortune() {

const weirdness = Math.floor(Math.random() * 4);

const isWeird = weirdness < this.weird;

if (isWeird) {

return this.fortunes.weird[

Math.floor(Math.random() * this.fortunes.weird.length)

];

} else {

if (this.score === 3) {

return this.fortunes.romantic[

Math.floor(Math.random() * this.fortunes.romantic.length)

];

} else if (this.score < 3 && this.score > 1) {

return this.fortunes.good[

Math.floor(Math.random() * this.fortunes.good.length)

];

} else if (this.score <= 1 && this.score >= -1) {

return this.fortunes.neutral[

Math.floor(Math.random() * this.fortunes.neutral.length)

];

} else {

return this.fortunes.bad[

Math.floor(Math.random() * this.fortunes.bad.length)

];

}

}

}

Data-driven nutrition

Nutrition info lives in a separate module, which kept the logic clean and made updates trivial:

import nutritions from "../data/nutrition.js";

game.cumulateNutritions(nutritions[dishName]);

Tests: small but meaningful

We wrote unit tests around deterministic parts of the logic (score/weird increments). That’s the right place to start in a project like this: get confidence in the “pure” logic before trying to test the DOM-heavy UI.

import gameObject from "../source/js/fortunes.js";

test("Score should be 1(Increment)", () => {

const testGame = new gameObject();

testGame.incrementScore();

expect(testGame.getScore()).toBe(1);

});

Even basic tests helped reinforce the habit: write code, verify behavior, keep moving.