Tritons RCSC is an IEEE-sponsored robotics club at UC San Diego that competes in the RoboCup Soccer Small Size League (SSL). The “cool part” of RoboCup is also the hard part: getting a full stack—AI → networking → onboard compute → embedded control → actuators—to behave like one system.

This repo is the chunk I worked on as TritonBot team lead: the runtime bridge that listens to AI commands from the SSL simulation environment, converts those commands into wheel RPM targets, and sends them to the robot’s embedded system—optionally with real-time analytics to compare “expected vs actual.”

For competition reasons, the repository is private, but I can share the architecture and core code snippets here.

What this repo does (high-level)

At a glance, the runtime loop looks like:

- Receive robot commands over UDP multicast from the AI/sim

- Decode commands via Protobuf

- Convert local velocity commands → per-wheel RPM

- Encode RPM → bytes + headers + action flags

- Send the packet over UART to the STM32

- (Optional) Read back telemetry and plot expected vs actual wheel velocities

Repo structure and why it’s split this way

interface/ # Networking + hardware interfaces

tritonbot_message_processor/ # “Math layer”: velocity conversions, PID

analytics/ # Plotting + saved graphs

proto/ # Protobuf decoders for SSL + TritonBot messages

archive/ # Deprecated experiments / older approaches

This separation mattered because it kept the codebase understandable under pressure:

interface/= “How we talk to things”message_processor/= “How we interpret commands”analytics/= “How we debug reality”

Core runtime: tritonbot.py

The main script loads config, binds a UDP socket, parses protobuf messages, generates wheel commands, handles dribbler/kick, and pushes bytes to the STM32.

Here’s the essence of that flow:

# tritonbot.py (simplified)

with open("config.yaml", "r") as config_file:

config = yaml.safe_load(config_file)

server_address = config["serverAddress"]

server_port = config["tritonBotPort"]

udp_socket = init_socket(server_address, server_port)

received_robot_control = Communication.TritonBotMessage()

setup_dribbler_pwm()

while True:

data, _ = udp_socket.recvfrom(1024)

received_robot_control.ParseFromString(data)

actions = received_robot_control.command

msg = action_to_byte_array(actions) # wheel RPM → bytes

header = bytes([0x11]) + bytes([0x11]) # packet header

if actions.kick_speed != 0:

kick = bytes([0x14])

else:

kick = bytes([0x69]) # “no-op” placeholder in this code

if actions.dribbler_speed == 0:

dribble_off()

else:

dribble_on()

packet = header + msg + kick

sendToEmbedded(packet)

empty_socket(udp_socket)

The big win here is reliability: everything in the loop is focused on “receive → compute → transmit” with minimal hidden state.

Velocity conversions: local motion → wheel RPM

The AI provides local velocity commands (forward/left/angular). To drive an omni/mecanum-style drivetrain, we convert that into individual wheel RPMs.

The heart of that is getVelocityArray():

# tritonbot_message_processor/velocityConversions30.py (snippet)

def getVelocityArray(heading, absV, theta, rotV):

relativeTheta = (theta - heading + 2*math.pi) % (2*math.pi)

vx = absV * math.cos(relativeTheta)

vy = absV * math.sin(relativeTheta)

d = 0.13

r = 0.05

B = [-math.pi/6, math.pi/6, 5*math.pi/6, 7*math.pi/6]

# compute wheel velocities, convert to RPM, apply gear ratio, rescale

...

return M

Then those RPM integers get encoded into a byte array the STM32 can read:

def valuesToBytes(M):

send = []

for i in range(4):

send.append(M[i]>>8 & 0xff)

send.append(M[i]>>0 & 0xff)

return bytes(send)

This module also includes helpers for analytics like converting telemetry hex back into RPM arrays (hexToRpmArray), which became very useful when tuning.

Hardware + networking interfaces

UDP multicast from AI (interface/ai_interface.py)

We use multicast so multiple listeners can subscribe cleanly, and we aggressively clear socket buffers so we don’t “lag behind” real-time commands.

def init_socket(address, port):

udp_socket = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_DGRAM, socket.IPPROTO_UDP)

udp_socket.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

udp_socket.bind((address, port))

udp_socket.setsockopt(socket.IPPROTO_IP, socket.IP_ADD_MEMBERSHIP,

socket.inet_aton(address) + socket.inet_aton('0.0.0.0'))

return udp_socket

UART to STM32 (interface/embedded_systems_interface.py)

This layer sends byte packets to the embedded controller and reads back telemetry with a simple header check (to filter garbage).

ser = serial.Serial('/dev/ttyAMA0', baudrate=115200, timeout=0.1)

def sendToEmbedded(message):

ser.write(message)

ser.flush()

return True

def readFromEmbedded():

header_byte = ser.read(4)

if header_byte == b'\x01\x01\x01\x01':

data = ser.read(8)

ser.reset_input_buffer()

return (header_byte + data).hex()

return

Dribbler control (PWM)

We had a couple variants depending on hardware/software stack. The “sysfs PWM” approach is very direct:

# interface/dribbler.py (snippet)

def setup_dribbler_pwm():

os.system("echo 2 > /sys/class/pwm/pwmchip2/export")

os.system("echo 20000000 > /sys/class/pwm/pwmchip2/pwm2/period")

os.system("echo 1000000 > /sys/class/pwm/pwmchip2/pwm2/duty_cycle")

os.system("echo 1 > /sys/class/pwm/pwmchip2/pwm2/enable")

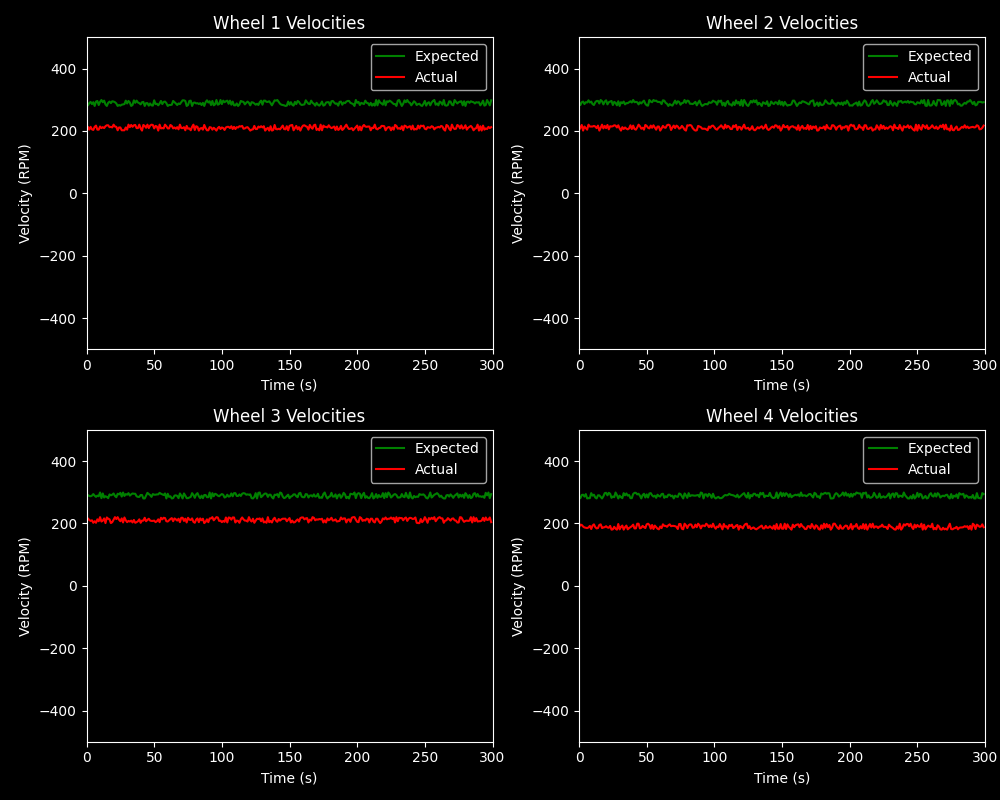

Real-time analytics: “Expected vs Actual” wheel speeds

When you’re debugging robots, the question is always: did it do what we told it to do?

That’s why the analytics/plotter.py module exists: it maintains four subplots (one per wheel), and can be updated continuously during a run.

# analytics/plotter.py (snippet)

self.fig, self.axs = plt.subplots(nrows=2, ncols=2, figsize=(10, 8))

def update_plot(self, frame, expectedVelocities, actualVelocities):

self.t.append(frame)

self.expectedWheelVelocities1.append(expectedVelocities[0])

self.actualWheelVelocities1.append(actualVelocities[0])

...

self.expectedWheel1[0].set_data(self.t, self.expectedWheelVelocities1)

self.actualWheel1[0].set_data(self.t, self.actualWheelVelocities1)

plt.pause(0.0001)

Some example outputs from analytics/saved_graphs/: